A Newly Released Book—The girls in the furisode: The two Tales

This multilingual (Japanese, English, Simplified Chinese, Traditional Chinese, and Korean) booklet contains a story of to A-bombed girls, who were cremated in their long-sleeved kimonos (called “furisode” in Japanese) put on after their death in Nagasaki.

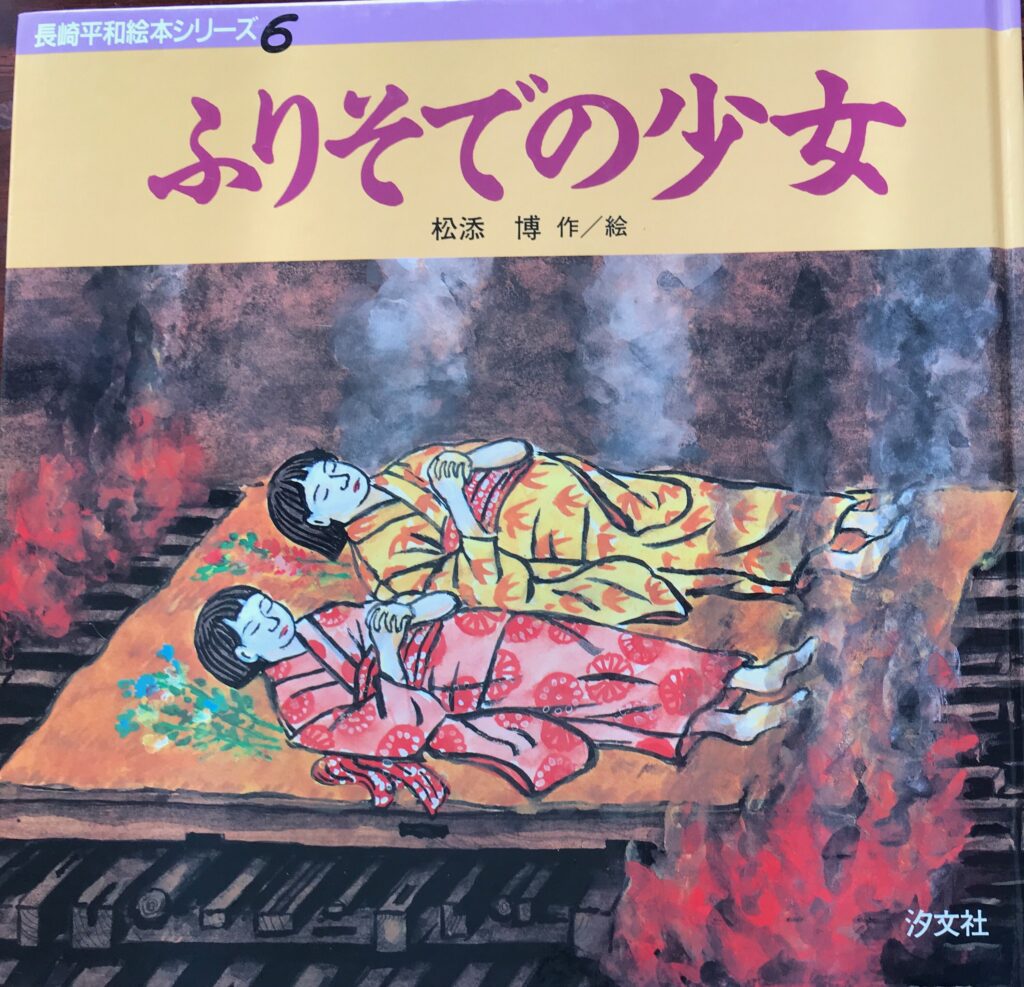

The story was originally published in a picture book, “The Girls in Furisode”, written and illustrated by Hiroshi Matsuzoe, an A-bomb survivor.

The newly released booklet also contains a citizens’ campaign to build a statue of the dead girls. This plan originated with junior high school students in Kyoto who heard about one of the girls from her mother. A citizens’ group started a fundraising activity to support students.

The finished statue was set up on the roof garden of Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum in 1996. This booklet was published by the Peace Study Club of Kwassei High School and students participated in the translation of Japanese passages into English. The booklet has a circulation of 5,000, available at Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum.

Nuclear Disarmament and the Peace Symbol

Nancy Meyer

The ubiquitous circular graphic called the Peace Symbol appears in popular culture on everything from earrings to bumper stickers. Everyone has seen it, almost everyone has displayed it, but few people know its origin.

History

The Peace Symbol was originally created to support nuclear disarmament in February, 1958, by a British artist named Gerald Holtom. It was first used in a large public display of 500 signs at the April 1958 Aldermaston March sponsored by the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War. The symbol was adopted by the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament as their official emblem.

Antinuclear movements have arisen at least twice since the creation of the Peace Symbol. In Holtom’s time, from the late 1950s to early in 1960s, nuclear test ban movements arose at nuclear testing grounds in the world. Twenty years later, from the late 1970s to 1980s, antinuclear movements swelled in Western Europe, where citizens protested the deployment of nuclear weapons by US Forces. Their slogan was “Euroshima”, which meant “Never Again Hiroshima in Europe”. The symbol has thus become firmly established as an international symbol of peace since the Cold War era.

While the Peace Symbol has become recognizable worldwide to simply represent “peace” its original meaning remains embedded in the design.

How it was Made

Holtom simply overlaid two semaphore depictions of the letters “N” and “D” for Nuclear Disarmament to create the familiar center.

Next, he simplified the human figures into straight lines. Finally, he drew a circle around the result, and the now iconic emblem was born.

Holtom was a conscientious objector in WWII who intentionally never copyrighted the design. Importantly, this universally recognized symbol of peace has resisted copyright attempts to this day; it remains free for all to use. This has undoubtedly contributed to its omnipresence in popular culture for over 60 years.

You can learn more about Gerald Holtom here. To find out more details about the history of the Peace Symbol, click here or here. To learn about the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, click here.