How We Made Justice Impossible for the 9/11 Accused

A retired editor and technical writer living in Nebraska, USA, addressed the audience of this year’s American Muslim Voice Multifaith Virtual Peace Picnic, held online on September 11. She is a member of September 11th Families for Peaceful Tomorrows and proofreader of English language for our project, LinguaHiroshima.

My organization, September 11th Families for Peaceful Tomorrows, is a non-profit comprised of family members of those killed on September 11th 2001. We seek to break the cycles of violence caused by war and terrorism.

We are especially concerned about actions taken as a direct result of the 9/11 attacks. This includes the now nearly-forgotten ongoing process of trying the men accused of involvement in the attacks at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba, or more simply “Gitmo”. In October of 2019 I had a chance to spend a week at Gitmo to observe the military commissions pre-trial hearings.

There is a beautifully written and very relevant children’s book called The Enemy by Davide Cali and Serge Bloch. I’m showing a photo of the book’s cover as I invite you to travel with me to a bizarre part of the world called Gitmo. I begin with an excerpt from my diary.

He was smaller than I expected. The man who probably designed the plan to murder my sister-in-law was quite short, only 5’4”, my height. I asked about this, and was soon handed a list of heights and weights of all 5 of the accused sitting in that courtroom. The man whose height matched mine, matched me precisely in weight as well.

And so I found myself, a person with zero presence on the world stage, staring at someone whose out-sized international stature was at utter variance with his physical presence, thinking, “We are the same in this respect. We would fit into the same clothing. We would literally see eye-to-eye if standing together.”

The courtroom we both occupy is at Gitmo, the location of the most infamous prisoners of modern times; 5 men accused of plotting the 9/11 attacks.

It might surprise you to know that the Gitmo military commissions proceedings are public. But the only public who can attend them in person are 9/11 victims’ family members, or members of a select group of 25 global non-governmental organizations, or NGOs. A dozen or more NGO observers and journalists have been visiting Gitmo weekly for more than a decade for this purpose. Peaceful Tomorrows members are both because membership in our NGO is restricted to 9/11 victims’ family members.

Why did I go? Did I go to see justice served? It certainly would not be served in a week, as it has not been for nearly 20 years. And there is no realistic expectation that it ever will be. Did I go to make a difference in any way for others? I was told that my presence there as an observer was to “see and be seen”, to hold my government accountable and “keep ‘em honest”. I was also told that I should tell my story when I returned.

Khalid Shek Mohammad was far from the robust, even burly, swarthy man I’d seen in the infamous photo published at his capture. I knew him immediately from the turban and long red beard depicted in drawings of the courtroom. The beard is dyed for religious reasons. KSM uses orange juice and berries for the purpose, the only things he can get.

His physical size is certainly no match for his global reputation. I kept going back to this in my mind.

“They all look so normal,” gasped the young woman sitting next to me when the 5 prisoners filed into the courtroom on the first day. I knew exactly what she meant. But by any measure, everything about Gitmo is unconventional.

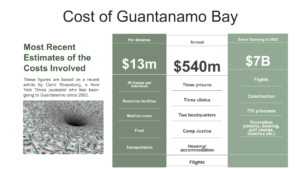

Gitmo has the unique status as rented US territory, and as such, there was a deliberate decision to hold these specific kinds of prisoners there – at a cost of $13 million dollars per prisoner, per year – in a place that one US government official called “the legal equivalent of outer space”. In other words, when jurisdiction is complicated by international ambiguity, anything goes. And indeed, it does.

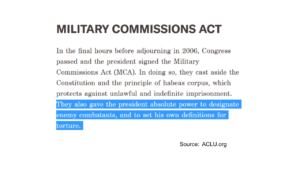

The 911 accused are at Gitmo to face justice. What would or could that ever be? The trial, whenever it does begin, is a capital one, meaning that conviction carries the death penalty. The accused are being tried as “non-privileged enemy combatants”, a special term meaning that they committed their acts within the context of a military conflict. In other words, their legal status is based upon the contrived notion that there was a war in place on September 11, 2001, but they are not entitled to the automatic protections accorded to soldiers or civilians in a theater of war. The “non-privileged enemy combatants” designation, created especially for these prisoners, is important because that is what allows the possibility of a death sentence.

Here are some of the questions I submitted to one of the 9/11 trial attorneys about the accused:

- Assuming they are guilty, have they already been punished enough via the years of brutal torture they endured at black sites? Would death be more punishment for them, or a release from punishment? Would it be a reward in their world view?

- How does trying these men and then putting them to death square with not trying Osama Bin Laden, but simply putting him to death? I have never understood the difference in due process between these cases.

Not surprisingly, I did not get answers to any of these questions. Beyond the fact that a defense attorney would be unwise to give any kind of substantive response, I rather suspect that none of the attorneys, regardless of the side they are on, really could come up with reasonable answers. No one can.

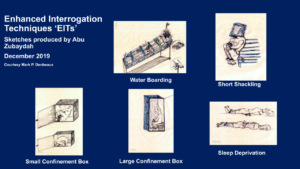

“The fact of torture changes everything”, Ammar al-Baluchi’s Lead Defense Attorney James Connell told me. Torture affects every single aspect of the trial, from evidence gathering to witness processing, to sentencing. It’s not just that it’s internationally illegal and morally wrong to torture people, nor that it is, in a very real and practical sense, of no useful value. Torture has a hidden cost to due process in that it absolutely ruins the ability to ever properly carry out justice.

BTW, I’d like to recommend a film called The Report, which came out in October, 2019, on the topic of torture of those rounded up after 9/11, how the US government tried to cover it up, and how it has spoiled any chance of justice for the 9/11 accused.

Right now well over half of the prisoners at Gitmo have not even been charged with a crime. Realistically, the Gitmo trial system is a hopelessly complicated legal, moral, physical, and philosophical quagmire.

Military commissions were intended to sort out what happened, and to properly process those accused of a massive horrible crime so that some kind of justice can be served. Yet one thing is well-understood and tacitly accepted by all who work inside these trials and observe them first-hand from the outside.

And that is that justice will never be served. It cannot be. Even without all the other challenges, there simply isn’t any version of justice that could ever be acceptable as appropriate to both the vengeful and the merciful, the law-abiding and the law-bending, the fundamentalist Christians and the fundamentalist Muslims, the victims’ families and those who lost no one.

The trial at Gitmo is fascinating. It’s also infuriating, devastating, confounding, interminable, and as widely ignored as it is maddeningly misunderstood. But it is, without any doubt, profoundly historic.

KSM and the 4 accused co-conspirators who daily sit in that courtroom allegedly did something that changed the world in so many, many ways for billions of people. But these men are remarkably unremarkable, just normal-looking middle-aged Arab men. Broken men from excessive and brutal torture, but ordinary human beings of flesh and blood nonetheless.

And this, I think is one of the significant things I learned at Gitmo: that no matter who you are, or what you look like, or where you live, or what you believe; what you choose to do with your time on this earth matters.

And we all want to do something that matters. Many of us feel a daily desperation to make a difference, a real difference in the world. Something big, and long lasting. I know I do.

But how do we do that?

Today, you get your pick of existential threats to work on. Anything you can do to avoid or mitigate nuclear war, global pandemic, or the climate crisis undoubtedly changes the world.

But just because what we do is not something big or earth-shattering, or earth-saving, or with worldwide impact, doesn’t mean it won’t have an effect beyond our lifetimes. It doesn’t mean we won’t leave a legacy of good, because we never know the ripple effect our actions take.

How about by simply recognizing and honoring the humanity of others in every single interaction? That absolutely changes the world!

To be clear: I have no sympathy for the extremist ideology and actions of those involved in the 9/11 attacks. But I do see the accused as human beings, as opposed to something bigger or scarier, an entity to be feared or reviled, as the media promotes. And in doing that I change their image, an important first step in promoting peace.

And that’s something I never expected to find out, much less announce publicly: Khalid Sheikh Mohamed and I are, in some ways, alike. We are two rapidly aging human creatures with strong ideologies and a big passion to do something important. Both of us have graying brown hair and weary brown eyes and stand at the same height in the same-sized mortal bodies. Importantly, he is no more or less powerful than I am, and never has been.

“We are so similar,” I thought while looking at a notorious mass murderer who shattered so many lives. “I really want to change the world too. Just NOT the way he did.”